This article is inspired from the Hospitality Resilience Series’ seventh session on “What we can learn from elite sport in developing psychological resilience”, held on May 20th 2021, hosted by Jonathan Humphries, Chairman HoCoSo, Chris Mumford, Founder CERVUS Leadership Consulting, Jon Hazan, Executive Coach ATLAS Coaching, with special guest Chris Bodman, Strength and Conditioning Coach, Performance Psychologist and Founder of LMNTARY Performance.

The Hospitality Resilience Series, the brainchild of Jonathan Humphries, Chris Mumford and Jon Hazan, was created as a community project aimed at supporting leaders in the hospitality sector to develop their own personal resilience and their inner immunity. The theory being that as individuals, we become stronger and healthier leaders when we share the pool of learning and experiences. This will not only benefit, but also engender greater resilience for the sector as a whole.

This episode, is dedicated to the topic of Developing Psychological Resilience for Sustained Success in Elite Sport. How is this relevant to hospitality professionals you may ask? The answer is simple. Pro athletes continually operate under pressure individually and as a team. They face all kinds of external challenges beyond their control such as fans, media, financial pressures, injuries… They also face internal challenges within their control such as mind-set, motivation, dedication, focus and performance. As such, and in parallel, the context applies to just about any kind of setting one could think of or even imagine. However, what is unimaginable, is the complexity and various dimensions that factor into what, at least from the outside, looks simple enough, but rarely ever is.

The most complex object in the universe

At the dawn of human history, man’s desire, instinct and later on, tools helped to regulate parts of our environment in pursuit of total control. While that quest thus far saw humanity reaching other planets, the inner workings of the main driving engine that made all these discoveries possible, remains to a very large degree a mystery. However, and before we even address that reality, let’s consider what we do know.

Adult humans have 206 bones. Every second, the body creates 25 million new cells. We have between 96,000-160,000 Km of blood vessels long enough to encircle the earth over three times. If you thought that is impressive, consider that humans are made up of 30 trillion cells, each with a specific structure and function. The brain contains 86 billion nerve cells and when calculating how fast it works, three variables come into play. These are, how many neurons we have, how fast neurons fire and how many cells each neuron connects to.

Our neurons are nerve cells that process and transmit electrochemical signals, similar to a miniature lightning bolt. Each neuron fires about 200 times per second and is connected to 10,000 other neurons. If we do the math, we arrive at the conclusion that 170,200,000,000,000,000 bits of information are transmitted per second, every second. Surprisingly though, that is not the most fascinating part. What is, is that %99+ of the time, the brain is doing the work in the background and unknown to most, we’re in full control of where we direct its focus.

Now consider the following example:

Portuguese footballer Cristiano Ronaldo steps onto the soccer field to the deafening cheers of tens of thousands of stadium fans and an audience of hundreds of millions throughout the world. That singular and relatively brief performance becomes a globally-shared reality whose results will have unimaginable ramifications on him and many watching.

In trying to encapsulate what’s happening inside an athlete’s mind in such instances, we consult our guest speaker Chris Bodman, Strength and Conditioning Coach, Performance Psychologist and Founder of LMNTARY performance. His work in elite sport and with some Olympic athletes has focused on finding ways to improve both the individual and the team’s performance at a physical and a psychological level. He teaches individuals to empower and improve their minds, bodies and behaviours through learning and development experiences.

Resilience vs. resilient

Setting the scene as to why some athletes and teams are better able to withstand the pressures of elite sport and attain their peak performances, whereas others underperform, Chris explained, “The process is basically an application in resilience. My work is centred on getting people in a sporting environment to think differently in order to tap into their full potential and then do the same for others. This kind of resilience, marries a person’s abilities to withstand pressure while maintaining function and focus. It’s a dynamic process based on natural interaction between individual and environment.”

Whether an athlete is part of a team or engaged in a singular sporting event, there exists a reactive element, which springs to light when that individual is faced with a situation of adversity. This calls on an athlete’s ability to bounce back or respond in a suitable and timely fashion, which brings the difference between resilience and resilient to the foreground. The former is a trait used to gain foresight and avoid pushing oneself over the edge.

On the other hand, “Being resilient, is a more fixed trait, which we either have or don’t. Looking from the outside in, we often see competitive athletes achieve great things and think they’ve got something we don’t. That may be a false pretence. It’s about how we can enhance and develop our own levels of flexibility in whatever environment we find ourselves in,” he clarified.

This process applies to almost everyone in varying degrees, especially individuals in top managerial positions. Highlighting another fundamental and oftentimes misunderstood aspect, is the fact that being resilient does not imply an absence or suppression of emotion. In reality and according to Bodman’s experience, the reverse is fundamental to develop resilience.

We oftentimes when considering individuals at the top of their game, find them to be cold, calculating, even inhumane in their ability to dispel their emotions in aid of maintaining control. It’s a method, according to continuously emerging research, that may be misleading. Finding time to practise is similar to finding time to introspect Bodman believes. Understanding performance is not different from understanding emotion. How do we develop some of these personal qualities and mindsets to enhance that resilience?

Developing resilience includes, optimism, a level of consciousness mixed with a pinch of extraversion. Also, understanding what our motivation is, where it’s coming from and how we respond to certain situations, is paramount. “Being mindful of these will allow us the ability to direct our attention and regulate that kind of arousal to eventually achieve that desirable outcome, especially in pressure or adverse situations.”

It’s that intrinsic interaction that opens the door to unlocking a person’s full potential. So, once a person arrives at that stage, gaining the ability to evoke and maintain the ‘challenge mindset’ by positively evaluating and responding to pressurized situations using custom-tailored techniques or strategies becomes central to the desired outcome. “That’s why understanding my thoughts, feelings and emotions at the right time and place is paramount to performing at my best,” remarked Bodman.

Shifting blame vs. taking charge

Drawing on those conclusions, Jon Hazan, Executive Coach at Atlas Coaching and a believer in the importance of real-world experience expressed his fascination by the way athletes face their greatest challenges then bounce back after suffering serious physical injury. In this context he wondered what quality or approach enable them to do so and emerge stronger from injury.

“Resilience, doesn’t necessarily suggest that an individual demonstrates it in everything they do. An athlete may show a high level of resilience in a training or performance environment, but then when injured, recovery might become a real challenge for them. In other words, just because we display resilience in certain situations, doesn’t imply we’re going to demonstrate that resilience in every situation,” clarified Bodman.

Bringing more specific elements into the conversation, Chris Mumford, Founder of Cervus Leadership Consulting and Head of Leadership Services at HoCoSo wondered how one maintains peak physical ability in conjunction with the mind in light of constant uncertainty?

Navigating uncertainty

In response, Bodman made two very critical distinctions, “There is so much that is out of my own control. So, if I’m focusing my attention on these things, then I’d me wasting valuable time, time I think I have, but in reality do not. In other words, why worry about things that are beyond my control when my real focus should be on the things that are. In that context, allowing ourselves room and time to interact with our environment becomes key. That’s why athletes who develop the best resilience have good self-awareness of themselves and their surroundings. However, diversity suffered previously in certain environments, allowed athletes to develop resilience in that area, whereas they might not have felt that kind of pressure in another dimension. That’s why if a certain approach proves successful in a particular situation, it might not be as successful in another.”

The effects of environment and mindset on performance

The response brought to light a more sobering reality, one that is all-encompassing, which Jonathan Humphries, Co-founder and Chairman of HoCoSo raised, namely whether the real issue is the athlete’s immediate environment itself as opposed to an entirely unrelated matter occupying the mind of so said athlete.

The answer, while unsurprising simple, could prove quite complex considering that, “The more we get to know people, the better we understand what all the dimensions are that come into context. Again, building relationships, having trust and being open (not suppressing emotion) are all important to the outcome of the process. Keep in mind that it’s not just about my performance, rather all these things that attributed to me being able to perform at my best. The key, is getting people to think differently,” Bodman explained.

The wonders of a custom support system

Mumford took an instant to reflect on that statement and was reminded of a time when the simple response of stocking up on resilience typically called for an individual to ‘toughen-up and get on with it’. Though that approach was received with mixed results, the question always was, what or even how, as a team, to better support an induvial.

Borrowing from a real-life example Bodman related the story of Vicky Williamson, a track cyclist who in January of 2016 had a catastrophic collision with another cyclist in competition resulting in significant injuries with the potential of paralysis. Her Olympic ambition was over, or so it was presumed. “Despite her serious injuries, she was determined to get back on the bike and compete at the highest level. In her mind, she still had unfinished business to see through. Her resilience and personal qualities were really important in the recovery process. But again, just that change in mindset can make all the difference. She, instead of dwelling on the things that happened, used her experience to ask, how can I learn from that, how can I grow and how can I continue to develop? The six to eight months her and I collaborated made all the difference between being realistic as opposed to being optimistic.”

Pushing that point, he delved into the intricacies of human emotion remarking that once that difference is observed, we’ll gain the ability to shift up and down that continuum when the need arises by gravitating between the risk and reward sphere. In no other environment is that more real than the military on which a host of organisational systems where built beginning with the school system.

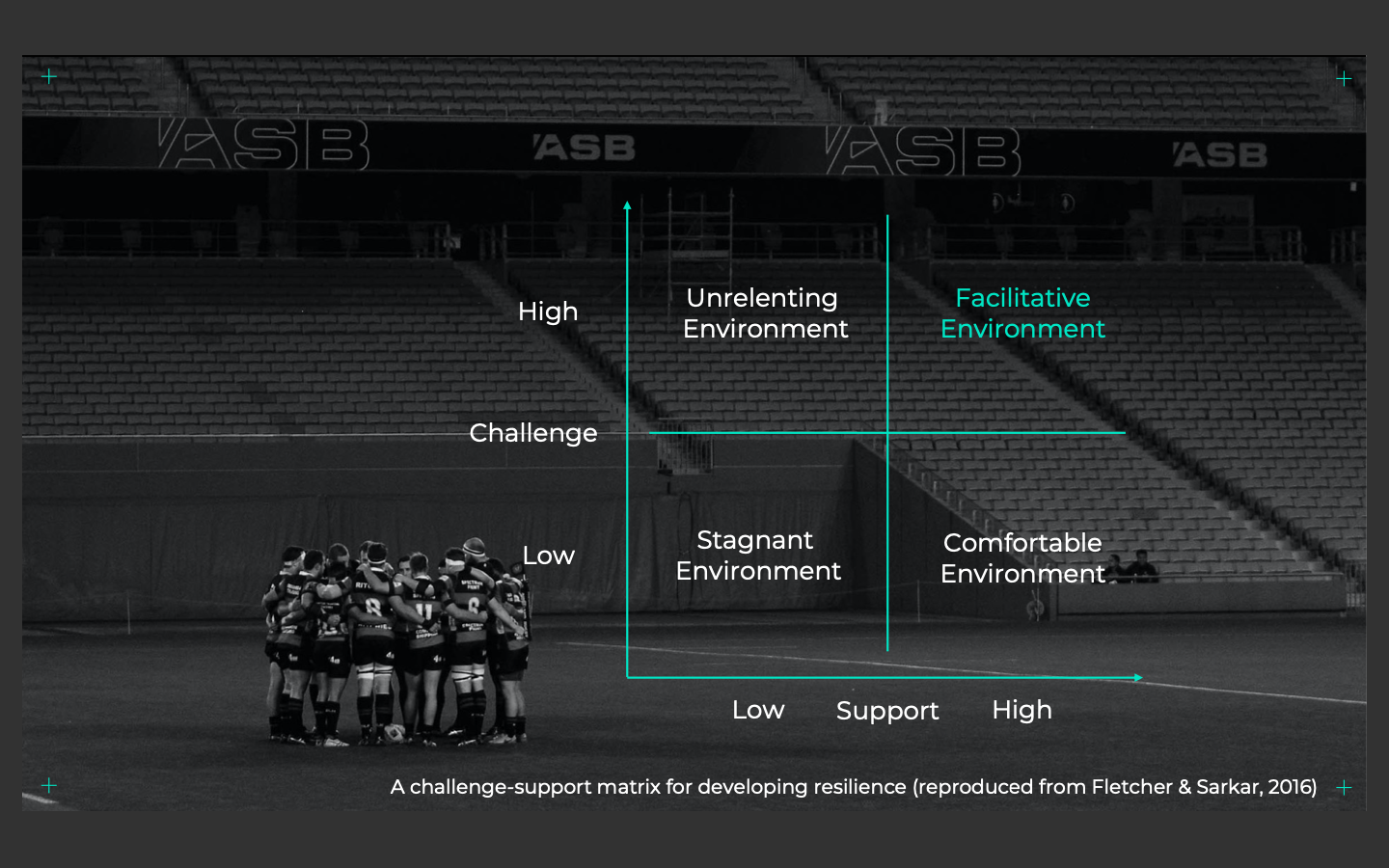

The four quadrants

Having served as commander in the British Army, Hazan noted how he learned, quite early on, that once that distinction becomes clear, the role a facilitative environment plays becomes instrumental to further bolster the performance of the entire group or team.

“We’re always kind of looking at the individual or the athlete and not necessarily looking how important their interaction with that environment is. But for the individual to thrive, we need to understand what the environment is doing to allow that to happen,” Bodman reasoned.

The below, breaks down the case into four distinct divisions.

Some resilience research suggests we’ve got a challenge on one axis and support on the other.

- In a low level of challenge coupled with a low level of support, the environment becomes relatively stagnant. This translates to an individual not pushing him/herself while also not receiving the necessarily support.

- If the support is high but the challenge low, then this is considered a comfortable environment, where the level of support outweighs the challenge.

- If the challenge is high and support is low, the environment becomes unrelenting and unsustainable. It also breeds unhealthy competition, which probably initiates a bit of a blame culture where individuals don’t feel supported.

- If both, the challenge and support are high, then the level of support received is aligned with the challenge. That’s the kind of collaborative environment that plays an optimal role on performance that automatically drives athletes to go that extra distance.

The four above-mentioned scenarios encompass every kind of imaginable context, which led Humphries to pause the most relevant question, namely, “How important then is it to create an environment where the athletes are kind of feeling safe and secure, even to fail and get back up and try again?”

The difference between short vs. long-term strategies

The answer, it would seem, reverts to what the objectives of an organization are. Generally, sport is measured on outcome most of the time. Often, the outcome overlays the facilitation of trying to develop an effective, sustainable and nurturing environment. “If success is deemed as winning gold and that’s not accomplished, then the strategy is obviously short-term. If the objective is to help that person to perform at their best, then I think that’s just as good a place as we can be,” Bodman rationalised.

Again, the support extended needs to align to that level of challenge, yet, when it comes to applying that same strategy to nurturing an entire team’s individual abilities, while having it operate as a single indivisible unit, the matter becomes far trickier. This is contingent on whether or not the vision is short-term and outcome based, or long-term and resilience based.

Highly-successful sport teams rely on the latter strategy to achieve the desired results using the shared leadership tactic. To add some context, Bodman gave the example of the England Young Lions cricket team. Comprised of 11 players, the team had not one, but a leadership group of five players. “What this setup allowed us to do was alleviate some of the pressure off the captain. In parallel, we were then able to clearly identify the individuals in action to surmise the strength and weakness of each all within the group operating at the same time. That’s really useful in trying to develop team resilience.”

To put matters into perspective and before parting, consider this. In the time it took you to read this ten-minute article, you travelled a distance close to 300 Km. (Earth revolving round itself). If you were to walk that distance, it would take an average person about 60 hours. On the other hand, we can travel continents in the blink of an eye through the power of our imagination courtesy of the human brain.

Now imagine what each of us could achieve if only we were more aware of the things transpiring around and within ourselves.

> Join the Hospitality Resilience Series‘ community on LinkedIn and on Instagram.

Our thanks to Yves for his time, his thoughts, and his excellent advice.

About the author

Jad Haidar

Jad Haidar

Leveraging over 20 years of writing as a seasoned journalist, Jad has interviewed globally reputed personalities in the advertising, communication and hospitality industries. He is a storyteller at heart, crafting balanced and informative articles for readers. He was the features writer for ArabAd and Hospitality News magazines in the Middle East for the past 10 years and is currently a webinar writer for HoCoSo. Before becoming a journalist, he spent 5 years teaching English. He holds a B.A. in English Literature and communicates in 4 languages.

About HoCoSo

HoCoSo are advisors with a difference.

We create tailor-made and innovative solutions for clients’ hospitality-led projects by bringing together the optimum team of sector specialists.

Jonathan Humphries, Chairman and Owner of HoCoSo, and his direct team specialize in the extended-stay, co-living, and hotel-alternatives hospitality market; luxury, lifestyle and boutique hotels; and resort developments in Europe, the Middle East and Africa (EMEA). Our strengths lie in the following core services:

- Product & Concept Creation, for portfolio & individual asset developments.

- Strategic Development Projects with a focus on new-market / new-concept business expansion planning, operator selection, market and financial feasibility studies.

- Transformative Asset Management for brand re-positioning, asset re-evaluation and concept re-structuring.

- Hospitality Education for companies and academic institutions, with a focus on bespoke course development, training and teaching.

- Workshops, Keynotes and Conference Moderating for boards, leading international conferences and incubators.

During the covid19 crisis, HoCoSo launched HoCoSo CONNECT, an initiative aimed at bringing the industry together to brainstorm and collaborate; HoCoSo CONVERSATION, a podcast channel encouraging the discussion with thought leaders from around the globe, for the hospitality industry; and, in collaboration with Atlas Coaching and Cervus Leadership Consulting, we also launched the Hospitality Resilience Series , a combination of online events, insights and discussions aimed at helping build your personal resilience and inner immunity.

Leave A Comment